Introduction

Sustainable investing has risen to the top of insurance companies’ agendas, and global interest in it is snowballing. Five years ago, it was mainly European insurers who were considering the relatively new concept called Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) integration as part of their investment criteria. But with climate change rapidly becoming a global concern, and COVID-19 changing how we live, the use of ESG factors has become a global phenomenon. Insurers from the US to Asia are listing sustainable investing as their top priority for 2022 and beyond.

Yet climate change is only part of the issue. Modern crises around biodiversity, food and water insecurity, inequality, human rights, and other major issues cannot be ignored. And then we have the pandemic, which has put a greater focus on the importance (and fragility) of human life.

In this paper, we focus on how insurance companies frame their investment strategy around sustainability and look at some of the challenges they face in implementing sustainable investing.

How are insurers approaching sustainability?

An overarching insurance theme seen globally is the public response to climate change and sustainability in general. The most marked reaction in the drive to align sustainable investing with public and governmental expectations has been the number of large insurers signing up to global initiatives. These include the UN-convened Net Zero Asset Owner Alliance, and the Net Zero Investment Framework, which both target net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

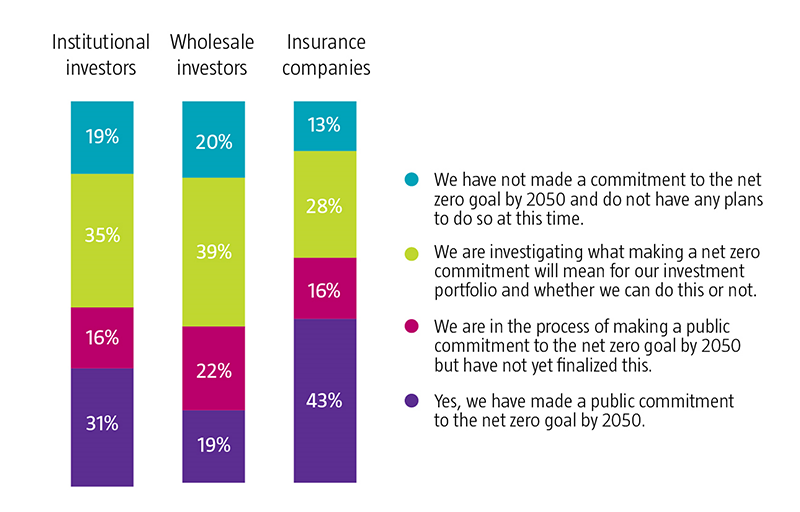

Robeco’s Global Climate Survey shows that up to 60% of surveyed insurance companies have already signed up to net zero or are in the process of signing up. Another 28% is in the process of investigating what making a net-zero commitment will mean for their investment portfolio.

Figure 1: How investors are approaching climate change - Commitments to net zero

Source: 2022 Robeco Global Climate Survey covering 300 of the world’s largest institutional and wholesale investors in Europe, North America, and Asia Pacific, representing a total of around USD 23.7 trillion in assets under management.

Insurers are approaching sustainability holistically, both through their protection and saving products as well as via their own general account. There are also different extents to which sustainability is addressed, from the more basic ESG integration into the general investment process, to the more explicit areas such as buying impact investing products.

What is particularly interesting and encouraging is that the largest insurers have begun to create their own sustainability agendas, on which they report progress annually. The scope of these agendas includes not only corporate social responsibility work, which tends to have a regional skew according to the locale of the insurer, but also what the company is contributing for the good of society.

How has the sustainability story developed over time with insurers?

Sustainable investing really came to the fore for insurance companies in the early 2010s, which coincided with the first real awareness that Earth is facing a climate crisis. During this time, insurers and other institutional investors began to introduce "responsible" policies, often focused on the exclusion of particularly carbon-intensive and/or socially disruptive industries. More explicit ESG integration policies have been put in place, and most large insurers have signed up to extensive engagement and voting programmes.

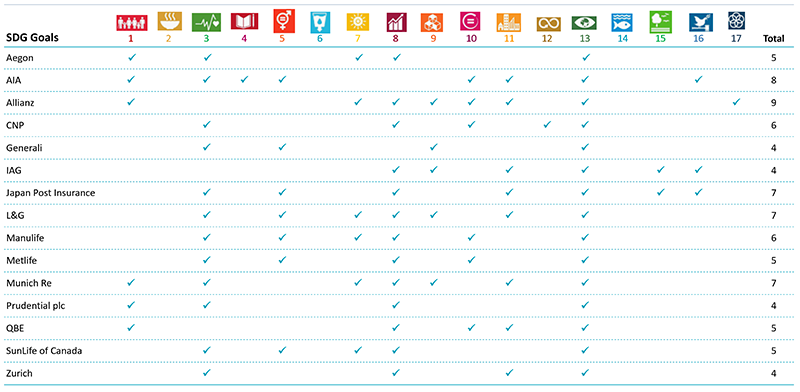

Focusing on impact investing has become a core tenet of an insurer’s sustainability and community engagement approach. It is not a completely new theme, though its scope and complexity has developed over the last decade. There has been a move from direct impact investing, through vehicles such as green infrastructure or property, to more indirect impact investing, which does not directly provide additional money to physical green projects, but supports wider sustainability themes. These efforts have gained in prominence since the introduction of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015.

Figure 2: Using the sustainable development goals as a focus

Source: UN

Common impact investments tend to be focused in a few key areas, such as green bonds and green infrastructure, and also through SDG strategies. The former are the more traditional impact investments, with the latter becoming more popular in the last few years. In fact, many insurers now frame their sustainability agenda through the 17 SDGs, and therefore tend to pick either the full spectrum of goals to invest in, or a few specific goals which reflect their sustainability aims.

The 17 SDGs have made impact investing much easier, as they allowed insurers to pick out the issues that matter most to them. To demonstrate how the UN SDGs are becoming central to insurers’ approaches to sustainability, the table in Figure 3 shows a peer analysis of some of the largest insurance companies globally and the SDGs they are looking to contribute to. These SDGs are published publicly within each insurer’s sustainability agenda.

Figure 3: A peer analysis of the SDGs selected by 15 insurers

Source: Aegon, AIA, Allianz, CNP, Generali, IAG, Japan Post Insurance, L&G, Manulife, MetLife, Munich Re, Prudential PLC, QBE, SunLife of Canada, Zurich. March 2021

Many insurance companies also use their impact allocations as part of their marketing efforts around sustainability in general. The larger insurers tend to release annual sustainability progress reports which highlight the work being completed through their impact investments.

How can insurers address sustainability on listed assets?

With a significant amount of exposure to listed assets, this is one of the key focuses for insurers in addressing sustainability in their investment strategies. Greater data availability has also made it a less onerous task when it comes to designing and implementing investment strategies.

There are three areas that can be focused on that are clearly measurable in terms of sustainability, and which are valuable to insurers for both their general account assets and savings products.

1. Sustainability-focused

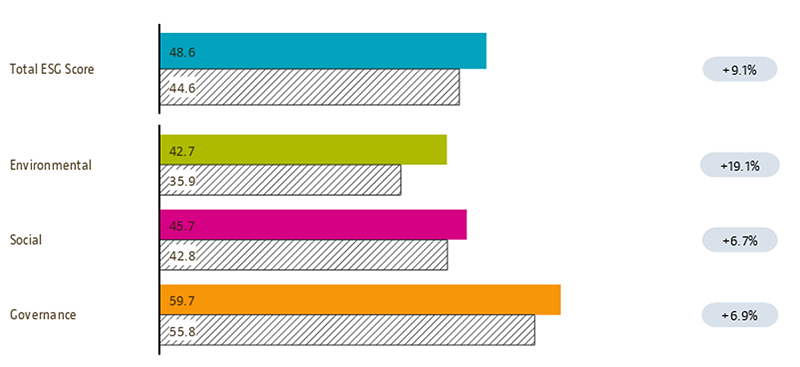

Sustainability-focused strategies have an explicit sustainability policy and aim to pick companies that score better on ESG. The investment universe remains diversified across sectors and regions. The result is a portfolio with a better ESG profile and an environmental footprint at least 20% better than the benchmark.

20% better ESG scoreOne way of achieving this is to integrate ESG in the portfolio construction process by ensuring that the total ESG score of the portfolio is at least 20% higher than the index. The ranking model proposes a high-ranking stock for inclusion when constructing the portfolio. It will propose another high-ranking stock if the portfolio would score below target on the ESG score. Companies with higher scores have a greater chance of inclusion in the portfolio as a result of this positive screening.

Figure 4: An example of ESG score comparison

Source: Robeco

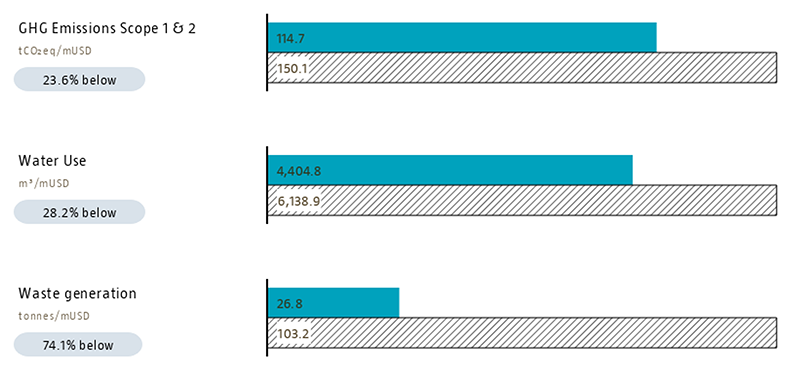

20% smaller environmental footprint

Another way of managing environmental impact is to impose an environmental footprint of the portfolio that is 20% smaller than the index. The portfolio’s footprint on four key quantitative environmental indicators—greenhouse gas emissions, energy consumption, water usage and waste generation—can be measured and set 20% lower than the index.

Figure 5: An example of impact metric comparison

Source: Robeco

2. SDG target

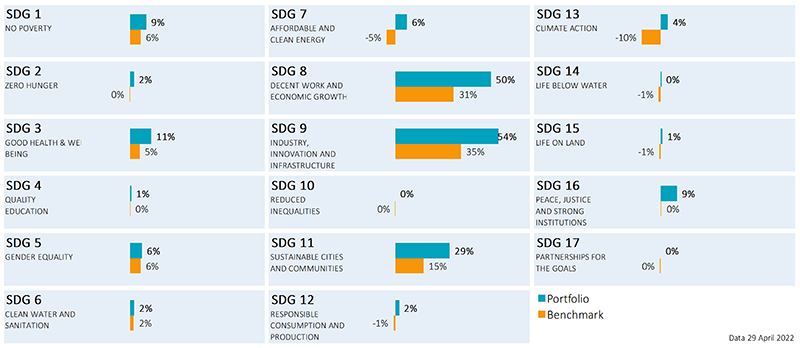

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) offer a focused form of sustainable investing, because investment can target a goal directly, or a theme encompassing several of the goals. Because many insurance companies focus on specific SDGs as part of their sustainability agendas, creating customised SDG strategies to target the relevant goals can contribute directly to reporting annual progress in sustainability agendas. One way of achieving this is to create a framework to assess a company’s contribution to one or more of the goals. A scoring system was then created that assesses both positive and negative impacts from the company’s operations. Positive scores denote positive contribution to the SDG. The scores are then used in the portfolio construction process where positive net contributions are considered. Figure 6 shows an example of how SDG metrics can be measured in a portfolio and compared against their benchmarks.

Figure 6: An example of SDG comparison - Contribution to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

Source: Robeco

3. Climate-focused

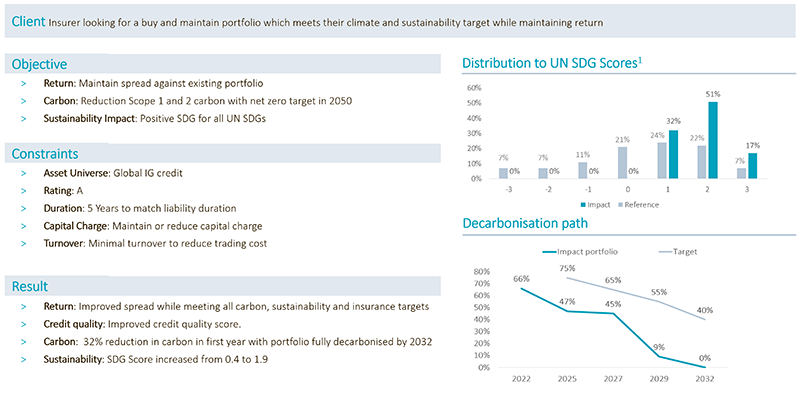

It is well documented that insurance companies are exposed to climate risks on both sides of the balance sheet. Decarbonising portfolios offers a means of reducing climate risks on the assets side, and perhaps unsurprisingly the biggest demand to do this is within the fixed income buy and maintain strategy, where insurers have long-term horizons and are limited in their ability to trade. With energy and utility sectors being the dominant carbon contributors at the long tenors, decarbonisation is no longer a straightforward quantitative exercise but one which involves active investment decisions. This along with integrating capital management for insurers makes this a complex decision process.

Figure 7: Case study: Optimising for climate risk in a buy-and-maintain bond portfolio

Source: Robeco March 2022

Private assets

While significant progress has been made in developing sustainable investment strategies for publicly listed assets, the picture is different for private assets with more entry barriers.

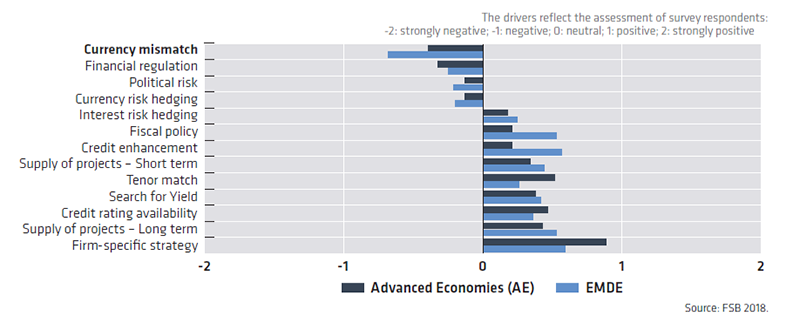

The Financial Stability Board (FSB) noted in 2018 that “Political risk, tax policies and non-financial regulation” are the main barriers to the demand for infrastructure assets. Supply issues and the lack of alignment between price and risk are other factors, but this paper aims to focus entirely on the regulatory, legal and accounting barriers faced.

Figure 8: Drivers of portfolio allocation toward infrastructure in advanced and emerging economies

Barrier 1: Capital regulations

Insurers are often subject to solvency rules that can act as a disincentive to invest in many sustainable asset classes outside of their region. Furthermore, there is generally inadequate encouragement by policy makers to incentivise insurers to invest in green assets, globally or locally.

In particular, the regulatory capital treatment of many ESG assets in US, Europe and Asia is typically the same as that of non-ESG assets, without a differentiated calibration of risk charges to reflect potential differences in risk profile and the benefits of these investments under likely future states such as a zero-carbon economy. For corporate bonds in particular, due to data and prospective modelling constraints, the process of assigning capital charges to different investments is still rooted in the historical default rates of those positions, leading to a lack of recognition of the advantages of sustainable investments as the effects of climate change continue to become more pronounced and the economic consequences of unsustainable investing become more dire

Many insurance regulators across the world are however working on medium-to-long term strategy to make sustainable finance a key feature of the asset portfolio of insurance companies. As an example, the US Treasury recommended that the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) and state regulators consider revising capital charges for infrastructure, although the recent proposed revision to capital charges under consideration by the NAIC’s Life-Based Capital Group leaves untouched the idea of differentiated risk charges by underlying asset type. Besides, the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission (CBIRC) recently updated its solvency rules for the assessment of credit spread risk with a reduction of 10% in credit spread risk factor for green bonds.

Emerging prudential standards such as new liquidity stress testing frameworks (e.g. NAIC’s liquidity stress testing in the US and similar proposals in Europe and the UK) for supporting macro-prudential oversight, are unlikely to be a constraint, as insurers tend to maintain significant excess liquidity relative to their liabilities. However, such frameworks reflect regulatory attitudes that appear geared towards promoting greater liquidity. This may work at cross-purposes with promoting ESG investing in developing regions, because those assets tend to be much more illiquid. Provided new macroprudential guidance on liquidity focuses on better monitoring of liquidity, and not necessarily increasing liquidity, then it may not much constrain insurance groups that invest in infrastructure assets as part of a coherent and well-managed asset-liability management (ALM) strategy.

The primary constraints for insurance groups are largely market-driven. This is a function of the prolonged low interest rate environment during which significant amounts of capital have been focused on a relatively limited supply of investable infrastructure assets. Recently, material infrastructure investments have been made in a few countries across the world, which could help increase the supply of investable assets over the near-to-medium term. In the US for example, the Biden administration’s infrastructure plans could help increase the supply of investable assets, particularly those that focus on “bricks-and-mortar” projects. Besides, US government support of infrastructure investing in wind and solar projects (e.g., debt guarantees) has had positive impacts. But there is still uncertainty about what form the Biden package will ultimately take in terms of tangible projects, particularly because the package includes certain less tangible investments in social programmes and education.

Along these lines, efforts are under way to promote private/public partnerships to promote infrastructure securitisation. The United Nations Capital Development Fund, for example, has been advancing blended finance solutions, which include:

- Creation of insurance products that meet the requirements of [Least Developed Countries] of providing long-term cash flow certainty and protections from extreme climate events

- A blended finance bond which is a mix of social impact bond and commercial bond that will be used to build infrastructure projects (UNCDF, 2020, p. 3)

These infrastructure bonds involve a collaboration among insurers, governments and the UN. Nurturing these partnerships will not only facilitate improve supply-side constraints, but will also support the regulatory and technical requirements needed to encourage increased allocations to environmentally sustainable infrastructure investments.

Barrier 2: Internal expertise

Another challenge confronting insurers is the lack of internal expertise and regulatory guidance on how to model heterodox ESG investments. Without this capability, insurers are not able to capture fully the lower risk position associated with nontraditional debt structures, nor their diversification benefits. If regulators wish to promote "green" investments, then more effort needs to be put into standardised practices for modelling these assets in economic, accounting and regulatory regimes.

Beyond the market-driven/supply constraints, there are some additional potential barriers on increased uptake of sustainable investing. The heightened policy maker focus on ESG and climate-related initiatives, while essential from a broader public policy and societal standpoint, could render certain projects less attractive, if these investments are not fully aligned with ESG objectives. In terms of insurance appetite for non-domestic investments, there are potential barriers in terms of both contract and legal certainty, as well as ALM disciplines. From an ALM standpoint, insurance groups with liabilities that are predominantly domestic in nature would need to determine whether exposure to foreign investments would be suitable to defease the corresponding insurance obligations. Depending on an insurance group’s global versus domestic footprint, the appetite for non-domestic investments would be limited if these projects reside in jurisdictions with greater legal uncertainty and foreign exchange risk. Bundling sustainable investments with certain insurance coverages, like political risk insurance, may help offset these concerns, but it is unlikely to materially impact willingness to invest, given the expense of such insurance and the requirements that must be met to receive payment under such policies.

Barrier 3: Regulatory guidance

Ultimately, while prudential standards are not a formal constraint, regulatory actions to differentiate the treatment of sustainable or climate-oriented investments with more favourable risk charges could nevertheless signify a public policy commitment to the asset class, which could have positive momentum effects on investing. This would also align the risk charges with the lower risk profile seen relative to traditional corporate debt.1 The former tends to exhibit decreasing defaults over time, and lower correlation with traditional asset classes, both of which support more favourable regulatory treatment. Additionally, there are other incremental regulatory changes that might modestly promote further investment.2 For example, if the NAIC Securities Valuation Office (SVO) were willing to predesignate its assessments for a particular infrastructure asset, then insurers would benefit from reduced uncertainty in capital treatment before making a commitment. As observed above, another neglected aspect of investing is the risk posed by climate change. While the property and casualty (P&C) industry is more concretely confronted with the effects of climate change, its risk only extends over a limited time horizon, so the long-term consequences are not necessarily of immediate consequence. Life insurers, conversely, have significant exposure to "transition risk." That is, long-term investments in less sustainable industries will face increased default risk as the costs and consequences of climate change become more apparent. Explicitly incorporating this transition risk into capital and ALM analyses would incentivise more investing in sustainable investments.

There are also barriers around outsourcing investment decisions. Under Solvency II, for example, transactions managed by development finance institutions and multilateral development banks (i.e., unregulated entities) are constrained. Many projects in developing countries are managed by such organisations. This functions as a barrier to increasing insurer investments in developing country projects and hinders a substantial source of private funding for such ventures, which are chronically underfunded. Unfortunately, there does not appear to be a dialogue between insurer regulators, insurance companies and development banks to promote the potential synergies.

There are also barriers based on domestic regulatory framework in certain developing countries that restrict insurers investing in certain assets, which could include infrastructure (to incentivise investment in local government bonds).

Barrier 4: Legal

One final challenge to sustainable investing in the developing world is the legal environment. There needs to be a clear legal framework in place between parties in the event of disagreement. Even in countries with strong rule of law provisions, insurers may be dissuaded from pursuing their legal rights out of political considerations. Insurance groups that develop a reputation for being open to conflict may find themselves receiving unfavourable treatment relative to other insurers or face more regulatory scrutiny. A recognition of the normative/positive legal rights distinction is critical to understanding the true costs and benefits of any investment.

None of these issues is intractable, but they do require substantial coordination between the public and private sector across different countries. Incrementalism has become an almost pejorative word in relation to climate change and climate scientists are in near universal agreement that current mitigation efforts are woefully inadequate to avoid the worst effects of a rapidly warming world. But the enormity of the problem should not dissuade small steps. Doing something to mitigate the effects of climate change is better than doing nothing, and with many people taking small steps, the collective distance covered can be vast indeed.

Conclusion

As sustainability objectives become a more significant—if not the central—part of an insurer’s policy in the next few years, we see sustainable investing as an essential tool to help insurers accelerate their progress in meeting their sustainable goals.

This combines with increasing interest from policyholders in accessing socially responsible insurance products to provide an opportunity for insurers to redesign their investment policies to meet these market trends.

This article was co-authored by Clara Yan ([email protected]) and Denis Resovac ([email protected]).

1 Though, again, the challenge here is that there is less history for these classes, which is partially why the risk profile may not have impacted ratings yet. An additional reason is also the level of granularity necessary to differentiate these asset classes from other investments of a similar credit quality.

2 See, for example, the guidance published by the NY DFS for managing the financial risks from climate change here:(New York Department of Financial Services, 2021)

Milliman, Inc. does not make any representations that the investments, products, or services described or referenced herein are suitable or appropriate for any reader. Many of the products and services described or referenced herein involve significant risks, and the reader should not make any decision or enter into any transaction unless the reader has fully understood all such risks and has independently determined that such decisions or transactions are appropriate for the recipient.

The reader should not construe any of the material contained herein as investment, hedging, trading, legal, regulatory, tax, accounting or other advice. The reader should not act on any information in this document without consulting its investment, hedging, trading, legal, regulatory, tax, accounting and other advisors.