On December 10, 2020, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Rutledge v. Pharmaceutical Care Management Association (PCMA) that states can regulate pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) reimbursement practices. This ruling could have major implications for self-funded plan sponsors beyond just the state of Arkansas where the case originated.

Key findings

The Rutledge v. PCMA case creates a clearer pathway for states to impose minimum thresholds on pharmacy (and more broadly provider) prices affecting reimbursement levels paid by plan sponsors. This means PBMs could be forced to pay pharmacies a minimum price for drugs that is higher than the amount they have historically paid.

PBMs generally use maximum allowable cost (MAC) lists to control generic prices for plan sponsors. Independent pharmacies have long held that MAC lists can lead to reimbursement that is less than the pharmacy’s acquisition cost for certain generic drugs, resulting in a financial loss to the pharmacy. This situation occurs more frequently at independent pharmacies because they have more volatility in drug level acquisition prices than larger chain pharmacies. Under Rutledge v. PCMA, the court upheld an Arkansas law requiring minimum payments for pharmacies from all health plans, including self-funded group health plans that enjoy preemption from state insurance regulation under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA).

This ruling puts upward pressure on generic drug costs in Arkansas (particularly in rural areas where independent pharmacy utilization is higher) and ultimately on plan sponsor costs. Most states have similar laws in place already applying to non-ERISA plans and this recent ruling may encourage the remaining states to extend reimbursement requirements to self-funded coverage through regulation or legislation, increasing drug costs beyond the borders of Arkansas. This ruling may force plan sponsors to reduce their contributions to employee health coverage costs and/or make benefit design changes if total plan costs exceed targets, though the increase in generic prices alone may not be especially noticeable when comparing them to typical pharmacy cost trends.

Background

Arkansas Act 900

In 2015, Arkansas legislators passed Act 900,1 which regulates pharmacy reimbursement rates for generic drugs for all health programs operating in the state, including Medicare, Medicaid, commercial plans, and self-funded employers. The key elements of Act 900 include the following:

- PBMs must update their MAC prices within seven days of a cumulative 10% increase in pharmacy acquisition price from at least 60% of pharmaceutical wholesalers doing business in Arkansas.

- Pharmacies will be allowed to challenge the MAC price if it is below their acquisition cost.

- If the challenge is upheld, the pharmacy will be able to reverse and re-bill affected claims.

The primary goal of this act was to support sufficient pharmacy reimbursement to Arkansas’s independent pharmacies.2 Pharmacy chains with large volumes of claims can typically address such considerations more directly with PBMs and/or wholesalers, but independent pharmacies may lack the leverage to ensure PBM reimbursements cover the pharmacy’s drug acquisition costs. As this law applies to self-funded plans covered under ERISA, it raises potential concerns for nationwide self-funded plan sponsors that typically avoid state-by-state regulation. The broad pre-emption of state law under ERISA can be described as prohibiting regulations impacting the health benefit plan selection process and, on this basis, PCMA (the trade group for the PBM industry) brought suit to overturn the law.

The lawsuit

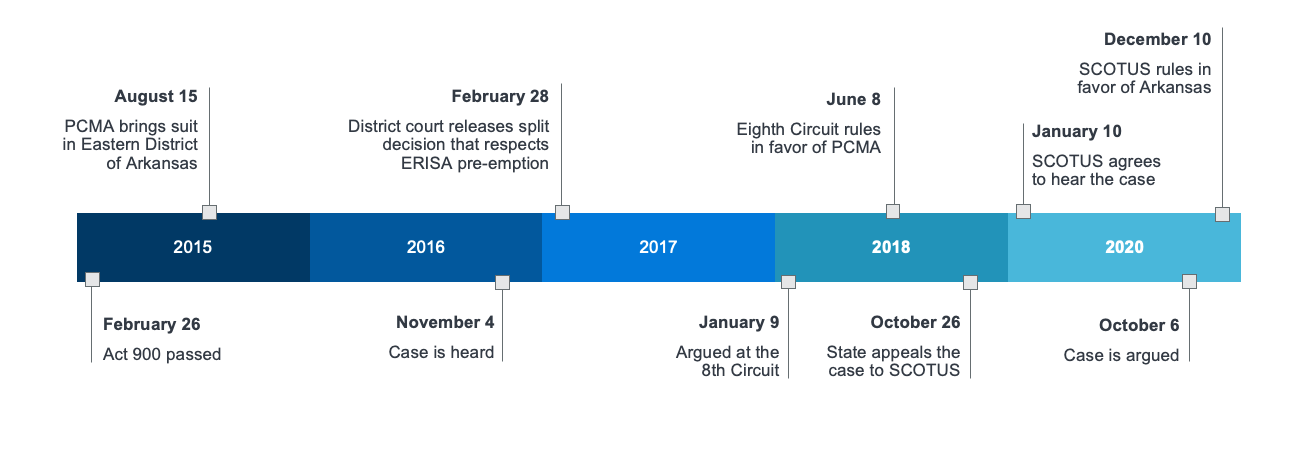

Initial developments in the case were generally supportive of PBMs, aligning with trends in judicial rulings related to ERISA preemption that have been supportive of third-party administrators operating benefit plans.3 As a key part of the health benefit plan offering, PBMs had a reasonable claim to be included under the current scope of ERISA preemption. This reasoning was part of the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeal’s 2018 ruling in support of PCMA’s position in the case. On October 6, 2020, the U.S. Supreme Court heard Arkansas’s appeal of the Eighth Circuit’s decision and, following a relatively short deliberation period, issued a unanimous ruling in early December 2020 that Arkansas’s regulation of PBM MAC prices is not preempted by state law.4 Moreover, the reasoning applied and the broad support behind the ruling would seem to support other state attempts to regulate PBM (and potentially even broader provider) practices in similar ways.

The direct effects on Arkansans

Most directly, this ruling affects Arkansas pharmacy reimbursement for generic medications. PBMs in Arkansas will have to manage their MAC prices in accordance with the state requirements, which could increase pharmacy costs for plan sponsors operating in Arkansas (particularly in the commercial market).

However, keep in mind this increase would be expected to be relatively small as a percentage of total plan costs. While generic drugs represented approximately 88% of 2018 pharmacy utilization on average, they only represent about 21% of pharmacy spend.5 As such, even a 10% increase in generic pharmacy costs would only increase total plan pharmacy costs by 2%, which equates to less than 0.5% of medical costs.6

Extended effects on the market

While this lawsuit explicitly addressed Arkansas’s law, at least 42 states have laws regulating the PBM industry in various ways.7 While this is the first PBM regulation case to reach the Supreme Court, other cases (including this one) were met with skepticism in lower federal courts. This ruling is likely to bolster state action to regulate PBMs, as it explicitly permits states to engage in reimbursement regulation that may raise costs to plan sponsors. As pharmacy costs continue to be a focus area for federal and state policy makers seeking to address rising health costs for payers and members, the regulatory permission provided may only embolden legislative efforts.8 These efforts could contribute to a broader rise in pharmacy costs, which could be more prominent in states with greater proportions of independent pharmacies.

Prior to this ruling by the Supreme Court, both federal district and appeals courts had generally ruled against states in attempts to regulate PBM activities.9 This ruling could cause states such as Iowa and North Dakota, and the District of Columbia, which had their own legislation limited or struck down by similar cases in the lower courts, to reassess their desired policies. As the ruling ultimately rejected the broadest interpretation of ERISA preemption by permitting actions affecting benefit plan costs, states may seek to extend regulation in the pharmacy space and may additionally seek to address other elements of health care cost (e.g., hospital and physician reimbursement) underneath the legal umbrella created by this ruling.10

Figure 1: Timeline

Regulations such as this also could eventually influence the management of pharmacy benefit programs. One possible outcome is MAC prices previously managed at a plan sponsor level instead become managed at a pharmacy level to limit the impact of upward pricing pressures to pharmacies with more volatility in drug level acquisition prices. The MAC prices at pharmacies with less volatility in drug level acquisition prices may be lower than the prices offered at pharmacies with more volatility. This could inevitably create price incentives for members and plan sponsors to utilize pharmacies with less volatility in drug level acquisition prices. In addition, this could create additional financial incentives for plan sponsors to adopt narrow networks excluding pharmacies with more volatility in drug level acquisition prices (e.g., independent pharmacies).

Expansion of these regulations in additional states could eventually influence changes in the supply chain to mitigate the volatility in drug level acquisition prices and resulting upward pricing pressures. In particular, even PBMs could have a vested stake in finding a pathway to assist some of these pharmacies in the drug purchasing, which could eliminate some of the risk related to reimbursement.

What the ruling does not change

The ruling itself permits Act 900 to remain as it regulates drug costs paid to providers, rather than key decisions made by the health benefit plan. This ruling does not grant states permission to regulate pharmacy benefit design for self-funded plans, nor does it explicitly grant permission to target self-funded plans through cost regulation. In fact, one of the key elements of Arkansas law is it applies regardless of the market in which the regulation applies. The ruling ultimately spells out at least one clear boundary to ERISA preemption—but that boundary itself is limited to regulation of cost across all types of coverage, which may limit the degree to which this case can be used to justify future state actions to regulate healthcare and health coverage.

Effects on members

Health insurance is a highly valued benefit provided by plan sponsors, but the costs of health insurance are an ongoing concern for both plan sponsors and members. While the direct effects of Rutledge v. PCMA are confined to the state of Arkansas, most other states also regulate PBM activities and states continue to look for avenues to address PBM practices they view as negatively affecting members and independent pharmacies. In general, these activities seek to limit PBM behaviors some states see as anti-consumer or anti-provider and, as such, these actions are likely to increase medical costs to some degree. This could put modest upward pressure on member cost sharing on generic drugs and/or plan premiums, particularly where plan administrators have strongly leveraged tools moving members to generic medications when available. How the members will experience this cost increase will largely depend on their pharmacy benefit design:

- For standard high-deductible health plans (HDHPs) where members are subject to a high combined medical and pharmacy deductible, most of the impact will be in the member cost sharing on generic drugs.

- However, many HDHP designs include a preventive drug list allowing drugs for common chronic conditions (e.g., diabetes and high cholesterol), in which case more of the impact will be in increased premiums with some impact to cost sharing from generics outside the preventive drug list.

- For plans with flat copay or coinsurance designs, more of the impact will be in increased premiums with some impact to cost sharing from generics priced below the copay.

Conclusion

As these regulations affect the price of drugs rather than plan design, resulting increases in plan costs may ultimately be realized by members in the form of higher premiums or higher member cost sharing, unless plan sponsors choose to increase their percentage contribution to health premiums—a rarity in practice these days. However, these increases may not be especially notable when compared to general health trends—2% cost increases in pharmacy costs due to increased regulation may not be material for plan sponsors that may have grown used to an average 4% to 5% annual increase in health costs.11 However, it may be more noticeable for large groups that already engage in significant cost management efforts if this and other state cost regulation schemes limit some of the prominent tools PBMs and plan sponsors use to limit growth in healthcare costs. Plan sponsors may want to estimate the impact to member costs and plan liability from these regulations and consider potential solutions to mitigate the impact on members.

1The full text of the bill is available at https://www.arkleg.state.ar.us/Acts/FTPDocument?type=PDF&file=900&ddBienniumSession=2015%2F2015R.

2See the Background section of the decision at http://planattorney.s3.amazonaws.com/file/1e494c28f008463993615c4eeaa4f200/planPharmaceutical %20Care%20Management%20Association%20v%20Rutledge6-12-18.pdf.

3One of the more recent rulings, Gobeille v. Liberty Mutual Insurance Co., held that a third-party administrator could not be required to contribute claims to a state's database because doing so would have a cost, and requirement of payment of this discrete cost would in essence compel a specific employer purchase decision in contravention of ERISA preemption.

4The full text of the ruling is available at https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/20pdf/18-540_m64o.pdf.

5Milliman’s 2018 Health Cost Guidelines™, Commercial Drug Trends Research.

6The 2019-2028 Projected National Health Expenditures shows that pharmacy spending was about 11% of total personal healthcare spending in 2018 across all types of health coverage, though this can vary by line of business. See the Health Affairs article by Keehan, et al., "National Health Expenditure Projections, 2019-28: Expected Rebound in Prices Drives Rising Spending Growth."

7Leduc, J.K. (March 1, 2018). State Laws Concerning Pharmacy Benefit Managers. Office of Legislative Research. Retrieved March 4, 2021, from https://www.cga.ct.gov/2018/rpt/pdf/2018-R-0083.pdf.

8The National Academy for State Health Policy has tracked 14 bills targeting pharmacy benefit managers in the 2021 legislative session as of January 12, 2021, per https://www.nashp.org/rx-legislative-tracker/.

9Lanford, S. & Reck, J. (October 5, 2020). Supreme Court hears Arkansas pharmacy benefit manager challenge today. National Academy for State Health Policy. Retrieved March 4, 2021, from https://www.nashp.org/supreme-court-hears-arkansas-pharmacy-benefit-manager-challenge-today/.

10Mann, R. (December 13, 2020). Opinion analysis: Court rejects challenge to states’ authority to regulate pharmacy reimbursements. SCOTUSblog. Retrieved March 4, 2021, from https://www.scotusblog.com/2020/12/opinion-analysis-court-rejects-challenge-to-states-authority-to-regulate-pharmacy-reimbursements/.

11CMS. NHE Projections 2019-2028 – Tables (ZIP), Table 17. National Health Expenditure Data: Projected. Retrieved March 4, 2021, from https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsProjected.