This article was initially published on September 29, 2020 using data through September of this year. It has since been updated with data as of November 2, 2020.

The California wildfire season in 2019 was mild compared to that of the prior two years: 2017 was, at the time, the state’s costliest year on record for the insurance industry. Then losses in 2018 shattered records for a second consecutive year. As the 2020 wildfire season again exceeds historical norms, insurers and policymakers must turn their attention from the literal fires to the figurative one: the threat—and increasing likelihood—that this escalating wildfire risk will result in a homeowners’ insurance crisis in the state of California.

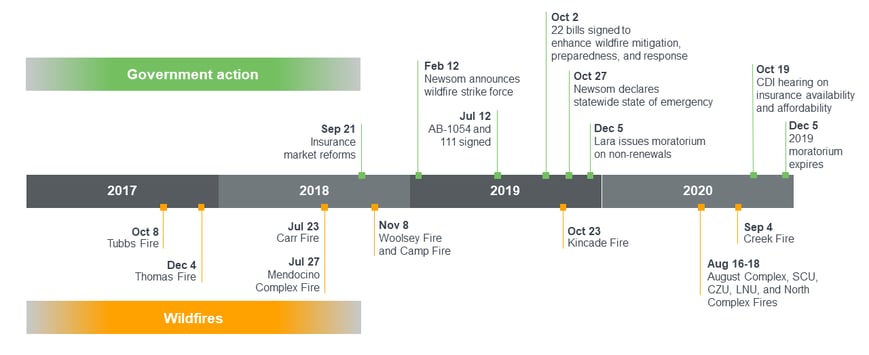

Figure 1

Known major California wildfires and government actions as of November 2, 2020.

Wildfires in 2020: Another record-breaking season

As of November 2, five fires, all of which began in August or September—the August Complex, the SCU Lightning Complex, LNU Lightning Complex, the North Complex, and the Creek Fire—placed among the top six in recorded state history in terms of acreage burned, surpassing all prior incidents except the now-second-ranked Mendocino Complex Fire of 2018.

At least for now, this year’s fires have been the state’s biggest, but not its most destructive. Since January 1, 2020, there have been 31 fatalities and 10,488 structures damaged or destroyed, less than the number caused by 2018’s Camp Fire alone, which devastated the city of Paradise, caused 86 deaths, and destroyed over 18,000 structures. So far, nothing on the scale of Paradise has repeated—but it could. The 2019 Kincaid Fire threatened over 90,000 structures but destroyed only 374. Thanks to over 2,000 firefighters and some cooperative weather, the Sonoma towns of Healdsburg, Windsor, and Geyserville were spared.

For homeowners, insurance is often the last line of defense against losing everything to wildfire. However, for many, this crucial financial backstop is rapidly becoming harder to obtain as insurers reduce their portfolios due to billions in losses and regulatory restrictions on reflecting the true cost of risk in the premiums charged. This withdrawal is creating an untenable situation for many Californians and efforts to address it are becoming an urgent priority for policymakers. One state action in late 2019 to prohibit policy non-renewals is set to expire in December 2020 for about 1.1 million homeowners. A similar state action in late 2020 is expected but based on our review of fires through early November is not likely to prohibit non-renewals for as many homeowners. Other longer-term solutions may be needed to maintain insurance availability for Californians. To understand the ongoing challenges, it is important to look at how recent events have shaped the industry.

Domino effects in the insurance market

In California, the insurance industry was upended by the record-breaking wildfires of 2017 and 2018. Using data up to and including 2018, Milliman estimated that home insurers incurred roughly $20.1 billion in underwriting losses due to the 2017 and 2018 fires—wiping out twice the previous 26 years of profit, threatening insurers’ balance sheets and, perhaps more importantly, resetting expectations on loss potential from wildfires.1 In response to this reality and the threat of escalating risk, many insurers have since implemented substantial rate increases. The cost pressures may be cascading. Reinsurers, who provide primary insurers with insurance for catastrophic events, are also expected to increase costs to reflect the new perceived risk of wildfires, which may subject insurers to further financial strain if those costs cannot be passed to consumers. Driven in part by the expectation that risk transfer costs may rise, insurers are also increasingly cautious about accumulating exposure in the high-risk areas most expensive to reinsure. In many cases, insurers are rejecting new customers and issuing non-renewal notices to existing policyholders. As a result, homeowners in those areas are either finding insurance to be increasingly expensive or increasingly difficult to obtain.

Legislative response

Lawmakers passed a wide array of reforms in 2018 and 2019, with goals to protect consumers and enhance wildfire safety and risk management. The sweeping reforms passed in September 2018 (e.g., Senate Bills 824 and 894 and Assembly Bills 1772, 1800, 1875, and 2594, among others) were aimed at supporting insured wildfire survivors after catastrophe and improving insurance availability in areas affected by wildfire. In July 2019, the state passed AB 1054 and AB 111, which established a $21 billion wildfire fund to facilitate investor-owned utility payments of wildfire-related liabilities along with the California Catastrophe Response Council, which oversees and operates the fund. In October 2019, the Governor also signed 22 new bills that sought to improve the state’s wildfire prevention, mitigation, and response efforts, mitigate climate change through clean energy policies, and provide fair allocation of wildfire damages.

Momentary stopgap

Of particular concern to insurers is SB 824—passed in late 2018 and effective January 1, 2019—which enables the Insurance Commissioner to prohibit issuers from canceling or refusing to renew (“non-renewing”) any residential property policy located in ZIP Codes “within or adjacent to [a] fire perimeter, for one year after the declaration of a state of emergency.”2 Existing law already prohibits cancellations or non-renewals of policies that have suffered a total loss—SB 824 expands upon this by including those not affected by, but in close proximity to, a fire for which an emergency was declared. In this way, the Commissioner can enable policyholders near disaster areas to maintain coverage for an additional year.

Within nine months of its effective date, Insurance Commissioner Lara announced the first moratorium under SB 824. Heavy winds and dangerously dry conditions resulted in several large fires in late October 2019, prompting Governor Newsom to declare states of emergency in Los Angeles, Sonoma, and Riverside counties, and eventually statewide. On December 5, 2019, the Commissioner invoked SB 824 to impose a mandatory one-year moratorium on non-renewals for any residential policies located in 177 ZIP Codes affected by wildfire occurring during this time (Figure 3a). He additionally called on insurance companies to voluntarily halt non-renewals statewide until December 5, 2020.

Milliman estimates that approximately 800,000 homes are located within what the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (Cal Fire) has designated or proposed as a “Very High Fire Hazard Severity Zone”3 —areas that are subject to conditions that can promote extreme wildfire—making them undesirable risks for insurance companies and likely candidates for receiving non-renewal notices. While the 2019 moratorium has prohibited non-renewals for about 200,000 of these homes this year, it would not be surprising to see high non-renewal rates among the over 600,000 ineligible homes in the very high hazard areas (Figure 2).

When the 2019 moratorium expires later this year, 1.1 million homeowners (nearly 13% of California homes) will no longer be safeguarded, and an uptick in non-renewals can be foreseen as insurers catch up on reducing exposure in the riskiest areas.

Figure 2

| Single Family Homes (in 000s) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2020 | |||

| Inside Moratorium | Outside Moratorium | Inside Potential Moratorium | Outside Potential Moratorium | |

| Inside Very High Hazard Severity Zone | 199 | 622 | 73 | 749 |

| Outside Very High Hazard Severity Zone | 902 | 6,763 | 580 | 7,085 |

| Statewide | 1,101 | 7,385 | 653 | 7,834 |

Figure 2 estimated the number of single-family homes in ZIP Codes included in 2019 and the possible 2020 moratorium on non-renewals,4 inside and outside Cal Fire Very High Fire Hazard Severity Zones in state and local responsibility areas. Housing counts reflect the estimated number of owner- and renter-occupied single-family residences based on estimates from U.S. Census data.

Moratorium revisited?

Governor Newsom declared several states of emergency in mid-August 2020 due to wildfires and extreme heat. Soon after, on August 26, 2020, Commissioner Lara provided insurers notice of a forthcoming additional moratorium on non-renewals for residential policies in any ZIP Codes within or adjacent to the recent wildfires. Figure 3b shows areas of the state where such a moratorium could apply based on areas burned since mid-August up until November 2. It is important to note these ZIP Codes only represent a potential moratorium. Any final moratorium and associated ZIP Code list would be pending announcement from the Commissioner.**

Although the total land area impacted so far by the 2020 fires is vastly greater than 2019 fires, many 2020 fires have occurred within less populated areas. Barring further major fires, the total number of homes impacted by the anticipated moratorium is estimated to be just over half that of the 2019 moratorium (Figure 2).4

Figure 3a

Wildfires in 2019 (red) triggered non-renewal moratoriums in 177 ZIP Codes (light blue).5

| Wildfire perimeters | Very High Fire Hazard Severity Zones | ||

| Possible 2020 moratorium ZIP codes | ZIP codes within 2019 moratorium |

Even with a 2020 moratorium, it is likely that an unprecedented number of homeowners living in risky areas could receive non-renewal notices. Furthermore, escalating reinsurance costs coupled with the impact of the last four years of wildfire activity could have a compounding effect on the already intensifying financial pressures insurers face. With escalating reinsurance costs that cannot be passed to policyholders, insurers face threats to long-term profitability unless they restructure their portfolios by strategically shedding some exposure. This market dynamic could accelerate the availability shortage and further push policymakers to take action. If the commissioner’s most potent tool is an annual non-renewal moratorium in certain areas, we can expect it to be used. But this is not likely to bring stability to the market. The set of homes in protected areas would be constantly changing, and whether a homeowner in a high risk area is likely to keep their insurance would depend to a large degree on luck. Those in high risk areas where no fire occurred remain subject to non-renewal.

Over the long run, mandatory non-renewal moratoriums are ephemeral. Lasting only one year, these measures represent mere moments compared to the horizons associated with a homeowner’s interest in their property or the deployment of an industry’s capital. Moratoriums place limitations on insurer risk management, leaving them with few options. They may cease to offer new policies, raise prices when possible, or non-renew policies in unprotected areas to compensate for the unwanted risk in protected ones.

It may be tempting for legislators and regulators to turn to more permanent controls that require insurers to accept or retain policies beyond their appetites. However, absent other counterbalancing reforms that address insurers’ underlying concerns, this approach in isolation has the potential of creating, if not accelerating, long-term contractions in the California insurance market.

Insurers will always manage their exposure to match their perceptions of risk, and uncertainty about whether they are permitted to withdraw from risky endeavors will affect their likelihood to engage in them in the first place.

If insurers sense regulatory uncertainty alongside the threats from imminent wildfires, efforts to keep Californians insured could reduce insurance availability rather than increase it … a consequence opposite of the one intended.

In search of durable solutions

In California, insurers are constrained in the way they set premium rates.6 Instead of being permitted to charge a rate that is indicated by the catastrophe simulation models widely used in private industry, insurers must use a simple minimum 20-year historical average to project losses for future catastrophic events. Beyond model use constraints and the exclusion of reinsurance costs from rates, California insurers may face hurdles to changing prices, even using state-prescribed methodologies. Insurers must submit rate proposals for regulatory review as a normal course of business. But in California, the review period can be particularly lengthy, and filings can be subject to costly public intervention and hearings. An insurer’s request for a rate increase may lead to their being forced to take a rate decrease, and effective dates may be delayed many months (sometimes years) beyond what insurers originally request.

AB 2167 and SB 292, a pair of bills introduced in mid-2020, represented a push to improve insurance availability in high-risk areas, partially by way of relaxing some of the regulatory hurdles faced by insurance companies. In at least one draft, the bills would have permitted insurers to use catastrophe modeling and reinsurance costs in ratemaking and request expedited regulatory review in certain counties, and in exchange, required insurers to underwrite some portion of properties in those counties. While this legislation was supported by insurance industry trade groups at various draft stages, it was opposed by several consumer advocate groups, citing reasons including higher premiums and removal of consumer protections.7, 8 Ultimately, the substantive elements of both AB 2167 and SB 292 were removed from the text in mid-August, signaling that no legislative reform is expected to come to fruition in 2020.

Despite the legislative standstill, the Insurance Commissioner continues to explore options. On September 16, 2020, Commissioner Lara issued a press release indicating his intent to administer new regulatory changes, among which could include creating insurance incentives for home-hardening standards, granting policyholders more transparency on their wildfire risk scores, and/or requiring insurance companies to file adequate and justifiable rates. It is difficult to gauge what impacts these broad strokes could have on the insurance market, as the devil is in the details. For example, mandatory, accurately-quantified home-hardening discounts could incentivize mitigation and reduce the state’s overall exposure to wildfires over the long term. But in the short term, those who cannot afford costly home renovations could see their insurance premiums increase as insurers offset revenues for discounts granted to those who can. As another example, forcing insurers to request fully adequate rates could aid in reducing insurer cost pressures, but doing so under current regulations could result in expensive and time-consuming rate hearings. Hastily implemented measures could be worse than no measures at all and presenting insurers with additional uncertainties may weaken an already shaky case to do business in California.

We remain hopeful that the path forward will be grounded in collaboration and a recognition of the dilemmas faced by all. Ultimately, policymakers must understand the ramifications of their efforts to keep Californians insured, and will need to look beyond temporary stopgaps that may mitigate pain in the short run but disguise the magnitude of the risk and delay the resolution of the root causes over the long run. As wildfires seemingly get worse with each passing year, the pressure to act is building, and meaningful, sustainable actions can’t come soon enough.

** On November 6th, 2020 Commissioner Lara released a list of over 500 ZIP codes in which insurers will be unable to cancel or non-renew residential policies based on the wildfires that occurred during declarations of emergency this year.9 We estimate these moratoriums affect nearly 1.6 million single-family homes, extending this temporary protection to almost 1.4 million homes that were not included in the 2019 moratorium. However, unless additional moratoriums are announced this year, about 825,000 homeowners included in the 2019 moratorium could lose their protection from non-renewals when that moratorium expires.

1https://www.milliman.com/en/insight/wildfire-catastrophe-models-could-spark-the-changes-california-needs

2https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=201720180SB824

3Cal Fire has classified these areas in state responsibility areas and released proposed draft classifications for local responsibility areas. Statewide GIS layers used in our analysis were received directly from Cal Fire April 2, 2020. Available online here.

42020 estimates are based on fires burning between August 18, 2020, and November 2, 2020. Estimates do not account for changes in housing counts from 2019 to 2020.

5Note that ZIP Code boundaries used in this analysis are representations of US Postal Service delivery areas and should not be considered de facto. No maps shown in this article should be used to determine a property’s eligibility for protections under SB-824. Wildfire perimeter data used in this analysis provided by Cal Fire and the National Interagency Fire Center.

6https://www.milliman.com/en/insight/the-california-wildfire-conundrum

7https://consumerfed.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/AB2167LetterJRHunter.pdf

8https://www.consumerwatchdog.org/sites/default/files/2020-05/AB2167Oppose.pdf

9http://www.insurance.ca.gov/0250-insurers/0300-insurers/0200-bulletins/bulletin-notices-commiss-opinion/upload/Bulletin-2020-11-Mandatory-Moratorium-on-Cancellations-and-Non-Renewals-of-Policies-of-Residential-Property-Insurance-After-the-Declaration-of-a-State-of-Emergency-Amended-11_6_20.pdf