The long-tail problem is the idea that markets experience poor supply-to-demand matching because of distribution inefficiencies, especially for nonstandard or niche products and services. In healthcare, the long-tail problem is often referred to as access barriers. A potential solution to access barriers can be telemedicine.

Distribution inefficiencies exist that are due to the physical problem of getting products to the customer. The evolution of technology has enabled many industries to reduce or eliminate the long-tail problem.1 To illustrate, consider the difficulty in renting an obscure movie while living in a remote part of the country. A movie rental store in a major city can stock many movies, whereas a store in a small town is only able to carry a fraction of those titles. The result is that individuals in more remote areas have a limited number of options. New technologies permit the delivery of goods and services to everyone regardless of location. For example, Netflix revolutionized the delivery of movies by effectively making a large number and variety of movies available to everyone with an Internet connection, regardless of geography, thus reducing the effect of the long-tail problem in movie rental distribution.

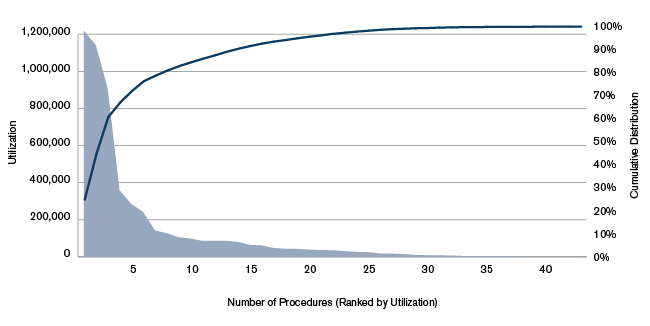

This problem permeates many areas of our economy and is especially pronounced in healthcare. Figure 1 below illustrates the long-tail problem in healthcare using Medicare utilization data. Abled individuals living in a major metropolitan area can access a broad range of healthcare services, though not always in a timely fashion or with the most appropriate specialists. Those living in rural areas, or otherwise unable to travel to an appropriate facility or provider, may be limited to only the most basic health services on a regular basis. While this may satisfy the healthcare needs for most people, most of the time, those individuals with chronic, complex, or rare conditions, or the frail, elderly, or disabled, may be more likely to experience access barriers.

Figure 1: Healthcare Access: Illustration of the Long-Tail Problem

Telemedicine is a mode of healthcare delivery that allows patients to remotely connect with a clinician for diagnosis and treatment. Some of the potential benefits of telemedicine include:

- Access to a broad spectrum of services for patients who cannot travel to a facility or doctor’s office

- Delivery of primary and specialty care to those living within developing countries

- Opportunities for clinicians to practice at the top of their scope of practice while gaining expertise and specialized skills

- More efficient use of provider capacity and increased operational streamlining

- Increased patient convenience and reduced absenteeism from work or school

- Improved care coordination and care management, especially for those with chronic or complex conditions

To understand current levels of telemedicine utilization, we reviewed recent available claims and enrollment data across the commercial and Medicare markets.2

Figure 2: Average Annual Utilization per 1,000 Medicare Beneficiaries or Commercial Members

Telemedicine use

- Utilization of telemedicine in both the commercial and Medicare markets has steadily grown in recent years (see Figure 2). This is likely attributable to several factors, including the increasing adoption of telemedicine through mobile devices and increased provider and patient comfort in remote healthcare delivery.

- Utilization of telemedicine is significantly higher for the Medicare population compared with commercial, as the dual axes in Figure 2 illustrate. This is partly driven by the higher utilization in general of an older population, but there are likely other factors at play as well. For example, Medicare covers telemedicine services for members located in rural areas, whereas coverage is not uniform and requirements vary on a state-by-state basis for commercial plans. In addition, there may be more services provided via telemedicine but they are not captured in the commercial data, which is due to inconsistent use of the modifier codes in the claims.

- Telemedicine utilization rates appear to be higher in Alaska and in the Midwest and Southwest regions of the country (see Figures 3 and 4). This makes sense, as a number of these states have large swaths of frontier and rural communities that require telemedicine in order to access to specialty care.

Figure 3: Telemedicine Utilization per 1,000 Medicare Beneficiaries, 2013

Figure 4: Telemedicine Utilization per 1,000 Commercial Members, 2013

- Average charge levels for telemedicine services are approximately 9.4% lower than the equivalent services delivered on-site for Medicare, and 0.9% higher for commercial plans.

- In rural areas, only about 0.08% of services that can be delivered to Medicare patients remotely are delivered remotely. For commercial plans, this drops down to 0.03%. These utilization rates are lower still for those living in major metropolitan areas. Note that claims data are useful for indicating utilization when services are covered and when an insurance claim has been filed. It is likely that actual utilization may be slightly higher, as some people may not have coverage for services and may be paying out of pocket.

There are five factors that have limited the shift of healthcare use to telemedicine, including:

- Coverage of telemedicine services and uncertainty regarding payment

- Clinical appropriateness and quality of care

- Technological limitations

- Legal and regulatory constraints

- Patient and provider comfort

Coverage of telemedicine services and uncertainty regarding payment

Laws and regulations related to coverage of telemedicine services vary in the commercial and Medicare markets; however, both markets have had increased flexibility in recent years. For example, Medicare covers telemedicine provided to beneficiaries in rural Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs) and nonmetropolitan statistical areas, with restrictions. For example, beneficiaries must visit designated originating sites to be eligible for coverage and only certain providers may provide remote telemedicine services. However, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) is seeking to encourage innovation and appropriate use of telehealth technologies under authority granted by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) and, most recently, the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act. For instance, next-generation Medicare accountable care organizations (ACOs) can seek waivers for originating site requirements as well as rural HPSA requirements, thus allowing beneficiaries to receive telehealth services in their homes regardless of whether they are in rural areas.4

Telehealth coverage policies in the commercial market vary based on state laws and regulations. State laws that govern private payer telehealth reimbursement policies range from mandating live and interactive video telehealth coverage to requiring parity for telehealth coverage with services received in person. Covered telehealth services are generally required to be delivered using live, real-time communication.

Even if coverage is required in a particular market, there is uncertainty over how providers will be paid for services delivered via telemedicine. Traditionally, for an insurance claim to be paid, the provider needs to record a valid “place of service” (e.g., a hospital, clinic, pharmacy, etc.). Uncertainty regarding the “originating site” (where the patient is located) and the remote provider site (where the provider is located) can be a barrier to delivery. Patients and the remote provider may be in an office, their homes, or a specialized facility for facilitating these services. Even though coverage rules are detailed by Medicare payment policies, commercial policies are evolving. And many healthcare providers are not likely to voluntarily perform telemedicine services if doing so places their reimbursements in jeopardy.

Second, the amount of reimbursement itself for telemedicine is in many cases unclear. Should a provider be paid the same for a given service whether it is provided in person or via telemedicine? In some cases, states have parity laws that require the same level of coverage regardless of modality. Should the originating site where the patient is located receive payment for assisting the patient setting up the visit? Possibly, but health plans have been slow to broaden fee schedules to permit this newer mode of delivery, outside of state mandates and access requirements. Health plans will only perceive telemedicine as a cost savings play if they can either negotiate lower reimbursement rates for these services or use it as a tool to manage chronic conditions more effectively. As a result, a swath of telemedicine companies have cropped up, promising managed care savings to health plans that contract with them.

Legal and regulatory constraints

Laws and regulations typically lag behind technological innovations. Most laws and regulations regarding the delivery of healthcare were established before the existence of technologies that are now common.

For example, state laws require physicians to be licensed in the originating site’s state; therefore, providing services across state lines may not be feasible. Organizations such as the Association of State and Provincial Psychology Boards, the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB), and the American Medical Association are exploring potential solutions to maintain appropriate oversight of practitioners while allowing for efficiencies and flexibility in licensing practices to improve access to care. For example, the FSMB developed an interstate compact that states can adopt to allow physicians to obtain licenses in multiple states. As of January 2016, 12 states’ medical boards have adopted the compact.5 A primary goal of the compact was to allow for increased use of telehealth across state lines while ensuring quality standards.

Telemedicine also presents legal issues from a malpractice liability perspective. For example, if services are provided across state lines, applicable jurisdiction and choice of law may be ambiguous.

Clinical appropriateness and quality of care

Providers and payers have had concerns regarding remote delivery of healthcare through telemedicine centering on whether the mode of delivery is appropriate to meet the patient’s clinical needs and whether it may compromise quality of care. For example, if a patient is obtaining services from a remote psychiatrist, are there protocols in place in case of a psychiatric emergency? Can standards of care be met? Will telemedicine compromise, improve, or be neutral in its effect on the patient-clinician relationship? The FSMB has published a “Model Policy for the Appropriate Use of Telemedicine Technologies in the Practice of Medicine,” and many state medical boards have adopted policies that affect licensure. These policies may cover issues such as informed consent, Internet prescribing, and establishing the patient-physician relationship.6

The extent to which services may be appropriate for remote delivery varies significantly by provider specialty. One area of practice that lends itself to remote delivery is behavioral health. Behavioral health services typically require no special equipment, such as scopes or monitors for vitals, and are easy to implement. For example, psychotherapy techniques rely on dialogue with patients that can be conducted via telemedicine.

Telehealth vendors that provide urgent and primary care typically limit services to those conditions that can be reliably treated through this modality and then recommend in-person visits for conditions that require more intensive care. For example, employers and payers that partner with American Well provide access to treatment of common complaints such as flu symptoms, upper respiratory infections, urinary tract infections, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and skin rashes.

Technological limitations

There are two types of technological limitations to delivering healthcare services remotely. The first is the actual technology necessary for the patient and clinician to communicate in real time. The second is the technology the clinician can use to remotely collect the patient information necessary for treatment and diagnosis.

Up until fairly recently, video communication technology was not prevalent or cheap enough to feasibly facilitate telemedicine on a massive scale. Now the majority of people in developed countries have access to a mobile device. The infrastructure necessary to facilitate patient-provider communication securely and privately has been largely built out as well.

Furthermore, in the developing world where these technologies cannot be taken for granted, telemedicine has proven capable of providing a level of care substantially above that which would otherwise be available. For example, there are new technology-enabled solutions, such as those that allow patients seeking care to visit a community health worker who has been trained in the use of relevant diagnostic devices. This worker has access to a mobile device that provides prompts on the questions to ask and the vitals to measure. The worker enters this information and transmits it to a clinician in a different country, who then makes a diagnosis or identifies additional information that is required. The patient receives a diagnosis and begins a course of treatment.

Patient and provider comfort

Provider comfort with telemedicine varies by clinician demographic, specialty, and experience in use of the technology. Patient comfort also varies by demographics, healthcare needs, and preexisting familiarity with the technology. Patient and provider comfort with use of telemedicine can be a barrier to adoption. However, with growing consumer comfort in using mobile and video-based technologies for various aspects of their lives, comfort in use of alternative modes for healthcare delivery will likely grow. Studies show that telehealth generally is becoming accepted by patients. And limited but evolving research indicates that live videoconferencing for mental health services can lead to patient satisfaction and improved outcomes.8

Telemedicine services can be beneficial for elderly and disabled patients who may be unable to leave their homes. As a growing number of tech-savvy Baby Boomers age into Medicare, we will likely see a growing demand for convenient access to healthcare services and thus a continued rise in the utilization of telemedicine services.

1Chris Anderson popularized the idea of the long-tail problem in a 2004 WIRED article entitled “The Long Tail.”

2For this analysis, authors relied on the Medicare Limited Data set, also known as the Medicare 5% Sample for 2013. The database contains Medicare Parts A and B fee-for-service claims for 5% of Medicare beneficiaries. This includes facility and professional payments for inpatient and outpatient hospital services, physician services, psychiatric hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, home healthcare and Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs), Rural Health Clinics (RHCs), and critical access hospitals. It does not contain Medicare Advantage encounters or Medicare Part D payments (i.e., for prescription drugs). We also relied on the Truven Health Analytics Inc. commercial claims and enrollment databases for 2014. Copyright 2015 Truven Health Analytics Inc. All Rights Reserved.

3This comparison was limited to procedure codes that provided at least 10 services in a year.

4Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Telehealth Rule Waiver. Retrieved April 7, 2016, from https://innovation.cms.gov/Files/x/nextgenaco-telehealthwaiver.pdf.

5Alabama, Idaho, Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, South Dakota, Utah, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming. See Federation of State Medical Boards (January 21, 2016). Six New States Introduce Interstate Medical Licensure Compact Legislation. Retrieved April 7, 2016, from https://www.fsmb.org/Media/Default/PDF/Advocacy/NewCompactIntroductions_Jan2016_FINAL.pdf.

6Financial Accounting Standards Board (December 2014). Model Policy for the Appropriate Use of Telemedicine Technologies in the Practice of Medicine. Retrieved April 7, 2016, from https://www.fsmb.org/Media/Default/PDF/FSMB/Advocacy/FSMB_Telemedicine_Policy.pdf.

7Montgomery, A. et al. (March 2015). Telemedicine Today: The State of Affairs. Ann Arbor: Altarum Institute.

8Richardon, L.K., Frueh, B.C., Grubaugh, A.L., Egede, L., Elhai, J.D. (2009). Current Directions in Videoconferencing Tele-Mental Health Research. Clinical Psychology. 2009: 16 (3). Supported by NIMH grant MN074468 to B.C. Frueh.